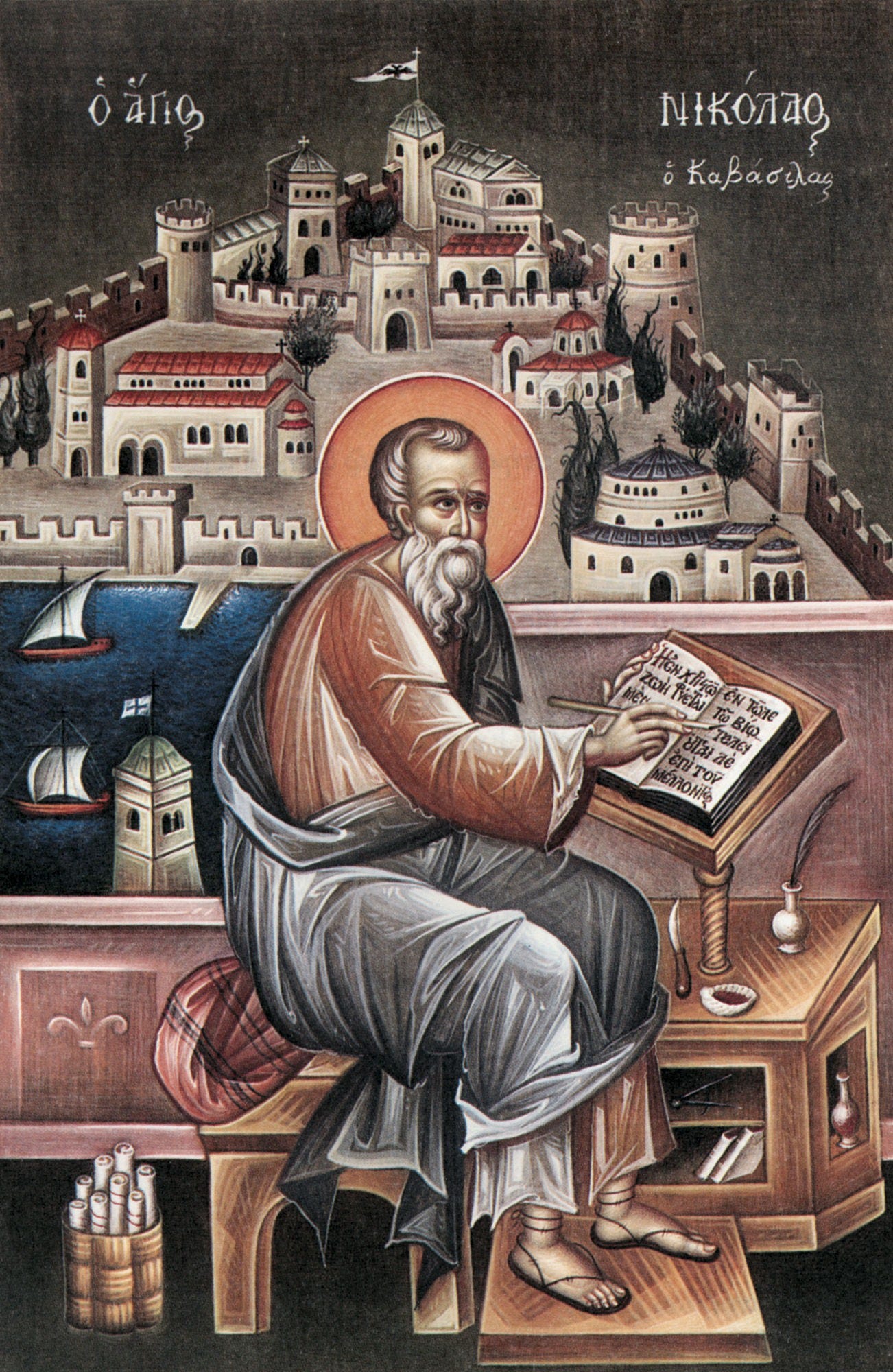

Today, the Church remembers the Righteous Nicholas Cabasilas, a liturgist and theologian who lived in the 14th century. He was from a noble family and, along with Saint Gregory Palamas and others, a member of the intellectual elite of Thessaloniki. The author of five important works on the sacramental theology of the Church, Nicholas Cabasilas viewed the sacraments, the holy Eucharist being the highest among them, as the foundational elements of a spiritual life. His main work, The Life in Christ, explores the meaning of each sacrament, and in its final chapters, is devoted to “sacramental asceticism” or ways of preserving the grace of the sacraments in the daily life of a Christian.

Avid consumers of self-help books may mistakenly assume that stress and anxiety are modern phenomena plaguing the Western man who is overworked, underpaid, and is helpless in the face of climate change and social discontent. Yet, there is hardly anything new under the sun. Below is a small excerpt from the chapter on the virtue of detachment dealing with the causes of anxiety in a person’s life in the 14th century Byzantine Empire and ways of addressing them.

We are anxious when it is uncertain whether we shall receive what we desire and when irrational concern has set in for the things which we want and for the means which we employ for their attainment. It is these things which can arouse anxiety and subject the soul to stress—excessive desire for what we seek and uncertainty about the attainment of that goal. But if we know nothing of the objects of our desire or see no prospect of attaining them, it is nothing grievous nor a source of anxiety. If we seek what we love as though knowing for sure that we will not receive it, no place is left for anxiety. For there is no care nor fear when anxiety reaches its limit, but the passion is simply that of grief for an evil as though it were already present. Since, however, none of the things which engender anxiety troubles the souls of those who live in Christ, they must therefore be set free from the evils of anxiety, for they do not cleave to any of the things of the present. In any work that they perform for the need of the body they always have some knowledge of the goal of their occupation, for they pray that the end of their labors may be that which pleases God, and they know very well that what is beyond their prayers readily deceives. These, then, are liable to suffer anxiety—those among the poor who wish for luxury and seek to possess more than is necessary for living, arid those of the rich who care more for money than for anything else. When the latter have it they fear lest it should suddenly be lost, and are distressed at their expenses, even when they spend money for what is necessary for the body. They carry their self-love to such an absurd length that they would rather have no benefit from their treasures and always keep them hoarded up rather than invest them for needed income, and that because they are afraid of expending it in vain. They are unable to have any confidence at all in the result of their labors, since they have not set their hopes in the hand of God, which is firm and enduring, but put their whole trust in themselves, their reasonings and their actions, which as Solomon says, "are worthless and likely to fail” (Wis. 9:14). But those who hate all worldly delights and despise all the things that are seen, use God’s laws as a light for all their efforts for their own sake or for others. Since they do all things with the hope which they have in Him, that they will meet with that which will benefit them, what need is there for anxiety? Why should they lie awake because of things which they already know are in good order? Since they do not merely seek the end which follows on their efforts, but also that which will be useful to them, they do not look ahead with anxiety, but know well that they will obtain that for which they pray. They believe that what happens to those who love is of all things the most advantageous and that for which they have prayed. They are like travelers who, when they have found a guide who is well able to lead them to their destination, will have no fear of being led astray nor any anxiety about lodging for the night. In the same way those who have committed themselves to Him who is able to do all things have taken leave of all cares of self. Since they have entrusted their life and all its care to Him alone, their soul is free from anxiety. Thus, as they have regard for that which alone is truly good, they can be anxious for the things of the Lord. So they fear and are anxious, if need be, only for that which pleases Him.

- The Life in Christ, Book 7, par. 6, The virtue of detachment

One important thing to note is that, unlike most celebrated theologians - and especially mystical theologians of the Church - who were monks and bishops, Nicholas Cabasilas was a layman. He was closely connected with the hesychasts and monasteries of his day, but scholars seem to agree that he was never a monk himself, giving us a rare and wonderful example of a layman’s life marked by sacramental mysticism and true asceticism.