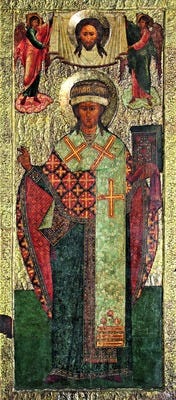

Saint Nikita, 19th-century icon

Saint Nikita lived at the end of the 11th-first part of the 12th centuries. His life story is long and multi-faceted, but one cautionary tale is worth recounting here. Being still a youth at his monastic tonsure in Kiev and having been warned against it by the abbot, Nikita made a decision to live as a recluse. Having no spiritual experience, he was easily tempted and fooled by the devil who appeared to the young recluse in the form of an angel. From this devil, Nikita received a gift of clairvoyance and an ability to interpret the Scriptures, especially the Old Testament. Both of these gifts appeared to be very much real, as he became known for predicting events before they happened and for explaining the Scriptures better than anyone else of the brethren, of whom at that time there were many learned ones, including Saint Nestor, the author of many works, including the Primary Chronicle.

However, the brethren were troubled by the fact that Nikita was not much interested in the New Testament and, for the most part, avoided talking about it with other monks. The brethren gathered together in fervent supplication for Nikita; and by their prayers, the Lord cast out the devil. Once he was freed from evil delusions, Nikita was so traumatized by the experience that he lost his ability to read and had to re-learn it anew. From that time forward, Nikita lived a righteous life, “giving himself to temperance, and a clean and obedient life, surpassing all by his virtue” (“A word about Nikita the Recluse,” The Kiev-Caves Paterikon).

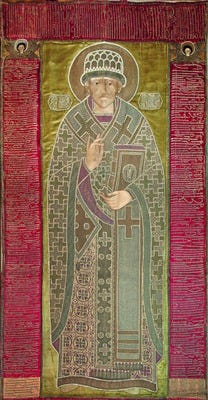

After some time, having been strengthened by his own humility and by the prayers of his brethren, and having “by reason of use [had his] senses exercised to discern both good and evil” (Heb 5:14), Saint Nikita was chosen to become the bishop of Novgorod in the year 1096. One curious note about Saint Nikita is that, uncharacteristically for Orthodox monks and bishops, he is depicted as beardless. This tradition originates in the 16th century following the uncovering of the holy relics of the saint in Saint Sophia’s cathedral in Novgorod, but the exact reason for it is not obvious.

Saint Nikita of Novgorod, 17th-century icon

These themes are ever-present in patristic experience: not all that glitters is gold, not all who appear to be angels are benevolent spirits, not all gifts are good, not all abilities aid in virtue, and pride is always a reliable indicator of corruption. But there is also hope: redemption is always offered to those who repent and humble themselves, and “the effectual fervent prayer of righteous [men] availeth much” (James 5:16). Nikita was fortunate to have brothers who loved him enough to fight for him. “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!” (Psalm 133:1)

Through the prayers of Saint Nikita the Recluse, may God deliver us from the delusions of the evil one.

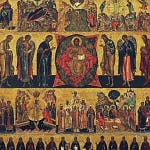

Saint Nikita, 17th-century shroud

If you liked this post, please share it with your family, friends, and even your enemies; and please consider becoming a subscriber. The yearly subscription is $50 or a little more than $4 per month. You can’t get a good copy of the Old Testament for that price.

Share this post